#10 - Surviving in a world of aggregators

Welcome to the new subscribers, and thank you all for the comments and feedback on my last newsletter — please keep them coming!

As I mentioned in my introductory post, my goal for this experiment is to sharpen my writing and thinking, to meet like-minded people, and to promote healthier discourse. If you know anyone who would be interested in the discussion, please forward this along or have them subscribe.

A quick note: As shown by my last few posts, I’m no longer exclusively exploring the viewpoints around hotly-contested debates. I still plan to write occasionally using that format, but moving forward, I’ll be writing more broadly about ideas in tech / business / policy.

📰 1 topic: Surviving in a world of aggregators

Today’s topic is inspired by Ben Thompson, a tech analyst whom I’ve looked up to for years. He has a daily blog about tech and strategy (aptly called Stratechery) — definitely check it out if you haven’t yet.

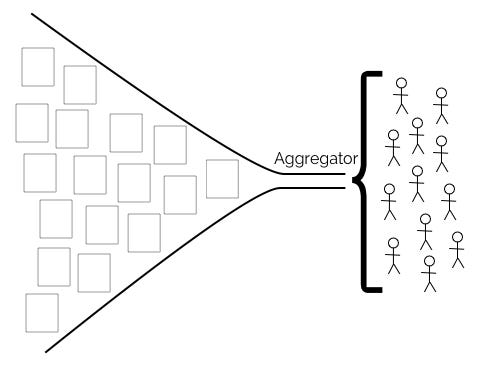

Ben developed a framework, called Aggregation Theory, to understand businesses in the Internet age. According to Aggregation Theory, powerful Internet companies succeed by sitting at the nexus between consumers and suppliers. On one hand, these companies exclusively control the user experience / relationship and deliver a product (at zero marginal cost) that garners massive usage. On the other hand, suppliers flock to the Internet company to get access to the company’s millions (billions?) of users. What results is a virtuous cycle whereby an increasing number of users begets an increasing number of suppliers, and vice versa. Meanwhile, the aggregator is extracting the majority of value from the value chain.

The problem, though, is for companies trying to survive in a world of aggregators. Indeed, suppliers eventually become modularized and commoditized as they come to Internet companies on those companies’ own terms. Look no further than Facebook. In a pre-Facebook world, news publishers won by controlling supply and distribution within a geography. Newspaper boys would be hired to bike around town with lugs of newspapers, and people would spend their mornings reading perhaps the local paper or the Times. The Internet blew this model out of the water. No longer is geography a lock-in constraint, and what’s more, anyone in the world can publish content! Facebook’s News Feed controls the eyes of billions of people, and traditional news publishers are now competing on the same terms with the likes (no pun intended) of puppy photos, weekend concert events, advertisements, and BuzzFeed. It’s no wonder that news publishers (and especially local news) are complaining that Facebook stole their lunch.

Below, I describe a few scenarios for companies to survive the onslaught of aggregators.

Subsidiary aggregators

I’ll define a subsidiary aggregator as one that captures a cohort of users from a larger aggregator yet operates in a similar value chain. This cohort must be large enough to hit the tipping point whereby suppliers begin coming onto the platform in droves, starting the flywheel of Aggregation Theory.

I find this strategy difficult to execute because larger aggregators have so much weight to throw around. Whenever they see a smaller competitor beginning to gain traction, they can merely copy or acquire the smaller company.

Perhaps the most successful (only?) example of a subsidiary aggregator is Snapchat, which captured a substantial share of teen social media usage from Facebook, or at least enough to become a multi-billion dollar company.

To understand how Snapchat was able to peel customers away from Facebook, recall that Facebook tried to copy Snapchat with Poke and Slingshot. Billy Gallagher, in his book on Snapchat, provided insight into why Poke / Slingshot failed and why Snapchat succeeded:

Poke was further hampered by the fact that teens were drawn to Snapchat because it explicitly was not Facebook, which was populated by their parents and collected everything they posted forever. . . [W]hy would [the teens] all pick up and leave Snapchat to share pictures on Poke when half the reason they had migrated to Snapchat was to escape the Facebook empire?

This insight is crucial. Snapchat had built a brand that organically made the incumbent Facebook less attractive to a large cohort of users. Snapchat grabbed many of those users for itself. It’s very telling that Facebook’s eventual successful response to Snapchat was to put ephemeral Stories in Instagram, which does appeal to teens and youth (unlike Facebook proper).

Co-existing aggregators

I’ll define co-existing aggregators as multiple aggregators able to survive in the exact same market serving the exact same customers.

Ride-sharing a la Uber and Lyft is the dominant example. Most people hailing a car have both the Uber and Lyft apps installed on their smartphones, and most drivers also drive for both Uber and Lyft.

To be honest, cognizant of the risk of narrative bias, I’m hesitant to state definitively why Uber / Lyft are currently able to co-exist, and I’m wary of generalizing to other markets. That said, here are my two cents / observations for why the equilibrium point in ride-sharing may have more than one aggregator. Perhaps this can be generalized to other markets capable of having more than one aggregator.

First, in ride-sharing, once you hit a certain level of liquidity between riders and drivers, any additional liquidity doesn’t matter. Anecdotally, once the wait time for Lyft is down to 4-5 minutes, I don’t really care that the wait time for Uber is a minute or two faster (or vice versa).

Second, although aggregators indeed modularize and commoditize supply, there is especially little differentiation in the supply side of ride-sharing markets to begin with. When you open Uber / Lyft, the cars are differentiated pretty much only by size (sedan vs. mini-van) and luxury (Toyota vs. Mercedes). Compare this with the level of supply differentiation on an aggregator like AirBnb, where you can pick a house based on size, location, aesthetic, host language, allowance of pets, existence of a parking / hot-tub / washing machine, and… you get the idea. In ride-sharing, the supply side is completely atomized, so again, once you have some tipping point in the level of supply, additional supply doesn’t really do much for you.

For these markets, once aggregators have aggregated a critical mass of users and a corresponding amount of suppliers, at that point, competition shifts to other vectors like price, brand, and user experience.

Building a unique brand, direct-to-consumer

A third way to survive is not to be a subsidiary or coexisting aggregator, but to be, interestingly enough, a supplier. The key is not to let the aggregator control your relationship with your users and reduce you to competing on the same playing field as every other supplier on the platform. Instead, the recommendation would be to cultivate a unique brand and go direct-to-consumer.

Of course, you still need to think about the economics of your business in relation to the strength of your brand. If you’re in the business of content publishing, which is extremely cheap to produce, you probably don’t need an absolutely killer brand to build a great business. This is a drum that Ben Thompson himself has been banging for years. The Internet makes it such that you can theoretically get exposure to the billions of people on the planet. As a content publisher, you only need exposure to a teeny fraction of a tiny percentage of that number, and you’ll still have a great niche of thousands of readers. Instead of posting ads on your site, or hoping for Instant Articles revenue from Facebook, you can put your content behind a subscription paywall, go straight to a customer’s inbox, and sustain a profitable business.

If you’re in a business with way higher costs, though, then you probably do need a killer brand. The streaming and movie-making businesses, for instance, are extremely expensive. Netflix is the aggregator here, and honestly, some film studios might do well to sell their productions to Netflix. After all, Netflix has the widest user base and can algorithmically recommend the best movies for those users to watch.

Disney, though, has pulled all of its films off of Netflix and decided instead to go direct-to-consumer. Disney can do this (and succeed in the long-run) precisely because of the strength of its brand. With Marvel, Lucasfilm, Pixar, and others, Disney attracts children and parents alike, who are sentimentally attached to these brands and are lining up to consume new content.

Conclusion

Although I’ve described three strategies above, these strategies are by no means exhaustive. Other strategies out there exist, and some parts of my analysis may not be applicable to certain industries. I’d love to hear your thoughts on this regard. What’s certain, though, is that there are ways to survive, and indeed, thrive in a world of aggregators.

📚 5 articles

COVID-19 known unknowns. Two reactions: (1) Epistemological modesty is an underrated virtue. (2) During COVID-19, there are so many things we don’t know, but when lives are at stake, I’d rather take over-protective measures and lighten up later than take under-protective measures and need to double down if things get out of hand. Unfortunately, you’ll receive a ton of backlash either way. Under the former approach, you’ll see people criticizing the government for “unnecessarily” shutting down the economy. Under the latter approach, you’ll see people criticizing the government for not doing more to protect people’s lives.

Coronavirus could create a new working class. “The poor got socially close, it seems, so that the rich could socially distance.” Interesting read.

How tech can build. Ben Thompson’s response to Marc Andreessen’s blog post: IT’S TIME TO BUILD. Andreessen’s post garnered a ton of praise and backlash this past week. Ben has a very even-handed response I very much agree with.

Why we can’t build. Ezra Klein’s response to Marc Andreessen’s blog post. Ezra’s angle is more about how institutions (especially political institutions) have failed us, something I also agree with and have previously written about. One of the reasons I’m disillusioned with government is that it seems like politicians are unable to collaborate, so you can't really get much done unless you're lucky enough to be in the majority. But then again, one principle that was beat into my head over and over again in constitutional law was that our government was designed to move slowly via separation of powers. Nevertheless, are we in an era of especially polarized politics? Lots to think about here.

Magic Leap cuts 50% of jobs. Augmented reality (AR) was extremely hot in venture capital in 2017. Magic Leap had raised $2bn and was thought to be the killer consumer AR headset for the future. Unfortunately, after multiple delays leading up to an underwhelming launch a couple years ago, Magic Leap been pretty much going downhill ever since.