#23 - Post-RBG politics; Is it wrong to be friends with conservatives?; Principles vs. policies

Post-RBG politics

Millions across the United States, liberals and conservatives alike, flocked to Twitter, the streets, and the news to mourn RBG’s passing last Friday. It was a rare moment of unity in an age of incredible division, with people reaching across the aisle to share their tears, stories, and admiration for one of the most intellectual and passionate legal figures of the past fifty years. Unfortunately, this taste of unity was fleeting, a bit too quick to even register the collective sighs of distress we all breathed in an already-terrible year.

Within hours of RBG’s death, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell indicated that the GOP-controlled Senate will vote on a replacement nominated by Trump before the end of this year, pouring gasoline on the raging fire of partisanship. Liberals are quick to point out that McConnell is committing intellectual suicide, contradicting himself when he blocked Merrick Garland’s nomination to the Court before the 2016 presidential election. Conservatives are more likely to call this an act of political strategy and heroism. McConnell, for his part, justifies himself by arguing that the difference between today and 2016 is that in 2016, the Senate was controlled by a different party from that of the president, whereas today, both Senate and White House are controlled by the Republicans.

Whatever you call McConnell and his actions, though, it’s clear that post-RBG politics will be more polarized than ever before.

For many Democrats, this might be the last straw, and we may see the Democrats changing the composition of (in other words, “court-packing”) the Supreme Court to undo conservative damage. As Chuck Schumer recently said, “Let me be clear: If Leader McConnell and Senate Republicans move forward with this [nomination], then nothing is off the table for next year. Nothing is off the table.”

Up until now, left-wing pressure for court-packing has been blocked by opposition from Democratic moderates like Joe Biden himself. But if the Democrats pack the court in 2021 (or whenever they next get a chance to do so), the GOP will surely retaliate with more of the same, the next time they get a chance. As Biden put it, “We add three justices. Next time around, we lose control, they add three justices. We begin to lose any credibility the court has at all.” On net, the Supreme Court becomes more of a pawn of political power rather than a check on political power, and society will be the loser at the end of it.

Is it wrong to be friends with a conservative?

With RBG’s passing, I’m also reminded of Justice Scalia’s unexpected passing in 2016. Scalia hardly garnered the same amount of love that RBG did. In fact, quite the opposite: Many liberals celebrated the “death of a terrible man.” They hated, and still hate, Scalia for his opinions.

While I disagreed with Scalia many times, I found myself always respecting him deeply as one of the clearest legal thinkers and writers of our time. Is it wrong for a liberal to respect and to be friends with someone like Scalia? Or, conversely, is it wrong for a staunch conservative to be friends with a progressive?

My personal take is no, and I arrive at my answer in three cuts. First, the tech angle (the only tech relevance of this entire post). I hold the general belief that innovation is one of the most important things a society can prioritize because it can grow the pie for everyone. Indeed, innovation is especially important in an age where global economic growth doesn’t seem fast enough to accommodate increasing consumption preferences, and millions (if not billions) of people are being left behind. Innovators, almost by definition, are those who have novel ideas about the world and on top of that, are bold enough to pursue them. Silicon Valley got its start precisely because it suspended disbelief in these new, crazy ideas. It made room for heterodox views and even views that were dangerous (‘disruptive’) to existing establishments. As someone who wants to foster a healthy environment for innovation, I’m more inclined to seek out those with views that cut against the grain and to at least hear what they have to say. In the world of coastal elites, many of these people are precisely the staunch conservatives.

Second, and relatedly, epistemic modesty is the principle that we don’t know nearly as much as we think we know, and we should be open-minded to new ideas that challenge our ways of thinking. Through this synthesis of new ideas, we sharpen our own viewpoints about the world and our understanding of our truth. RBG herself was famously (infamously?) best friends with Scalia, even though the two were polar opposites in terms of their political beliefs and dispositions on the Court. One of the reasons for this unlikely friendship was probably because Scalia sharpened her ideas. In the 1996 case, United States v. Virginia, which finally allowed women to attend the Virginia Military Institute, Scalia sent Ginsburg his still-unfinished dissent as quickly as possible to give Ginsburg enough time to respond in her majority opinion. “He absolutely ruined my weekend,” Ginsburg said, “but my opinion is ever so much better because of his stinging dissent.”

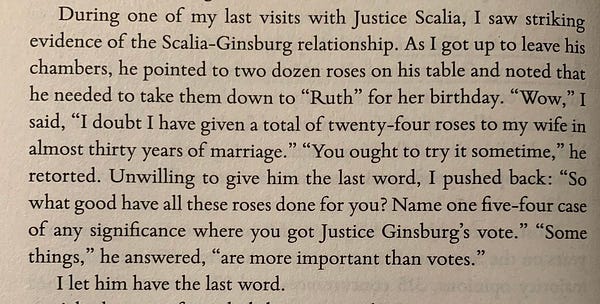

Finally, friends are more than politics. Here, too, we might learn a few things from RBG and Scalia. Eugene Scalia, Justice Scalia’s son, recently wrote an op-ed post about his father’s friendship with RBG, saying that the two “worked at the same place. They were both New Yorkers, close in age and liked a lot of the same things: the law, teaching, travel, music and a meal with family and friends.” Here’s another touching story about the two:

Some things are more important than votes. Put differently, I’m friends with someone not necessarily because he’s a liberal or conservative, but because we bond over other commonalities, attend and enjoy events together, have fun and interesting conversations, etc. Of course, there’s a sense in which this sentiment can be taken too far. At an extreme, I would not be friends with a Russian spy looking to undermine the United States, no matter how many other commonalities we share. So how and where do we draw the line?

Principles vs. policies

Here’s a helpful framework I’ve been mulling over to answer that question. A couple weeks ago, I wrote about principles:

Principles are clearly-stated priorities that you adhere to, live by, and try to advance. You have a stack-ranking of principles, and sometimes you forgo a lower principle in order to advance a higher principle. For instance, a BLM protester may value the principle of peace and order, but just because she protests in the streets, blocks traffic, and creates disorder, is she then necessarily unprincipled? Is she committing some form of intellectual suicide? Not necessarily! Racial justice may just be a more important principle for her.

Principles, though, are different from policies. Policies are particular proposals or actions you take to further your principles. While peace or racial justice might be principles, defunding the police might be a particular policy in line with those principles. Principles are amorphous, abstract ideas while policies are narrow, concrete actions. You derive your policies from your principles.

In an ideal world, you know your principles perfectly well, and you’re able to know others’ principles perfectly well. Moreover, you know what principles are, for you, non-negotiable. For instance, if my top, non-negotiable principle is the flourishing of the United States, I couldn’t be friends with someone who opposed that. Similarly, Ginsburg and Scalia had many differences, but they, too, shared a non-negotiable principle that united them. “We were different, yes, in our interpretations of written texts,” said Ginsburg, “yet one in our reverence for the court and its place in the U.S. system of governance.”

The problem, in this imperfect world, is that taking the time to introspect, to know your own principles, and to delineate your non-negotiable principles is hard enough, let alone getting to know other people’s principles. Instead, we rely on people’s policies, which are much more ascertainable, as proxies for their principles. There are three difficulties with this. First, the proxies themselves are imperfect, and someone else’s policy, taken in isolation, often gives you only a fragmented picture of their principle stack. The knowledge that someone supports a policy will, at most, give you insight into maybe a couple of her principles and maybe the relative ordering of those principles. To know her full principle stack, you’ll need to piece it together from a bunch of her policies. To be fair, some extreme policies (e.g., support of genocide) give you more clarity about one’s principles and whether those principles conflict with your non-negotiables. Those extreme policies themselves are, then, non-negotiable. Second, just because a person identifies with a political party or candidate doesn’t mean you automatically know all the policies that that person supports. And third, to make things more confusing, two different policies can actually be in service of the same principle! For instance, I know two people who both value the principle of racial justice, but one is against the policy of abolishing the police, and the other is for it. From the policy alone, I can’t jump to any quick conclusions about the two individuals’ principles and whether they necessarily conflict with mine.

The general trend in the United States is that our non-negotiable principles have gradually turned into non-negotiable policies. My sense is that the coastal elite hostility towards conservatives rests upon a disagreement over these narrow, individual policies rather than a disagreement over the broad principles behind them. It rests upon the self-confident belief not only that my policies are right but also that those who don’t share my policies are morally corrupt. Are we willing to suspend disbelief for just one moment to see that the other side might be trying to achieve the same goals in a different way? Are we willing to even consider the possibility that we might not be right?

In 1986, the Senate confirmed Justice Scalia to the Supreme Court by a unanimous vote of 98-0. The Senate confirmed Justice Ginsburg six years later 96-3. Although I wasn’t alive during that time, I have a strange sense of nostalgia for it, a longing to sit in front of a sepia-colored large-boxed television to watch the country come together, confident that the future of the Court, and indeed the nation, would be in capable hands. If Scalia or Ginsburg were put back in front of the Senate today, I’d guess that votes would split cleanly across party lines. Amidst all the political drama of the past 10 years, we’ve lost a sense of unity as a country, and it disheartens me. Politics itself has become non-negotiable. Perhaps I’m naive to think that we don’t need to sharp-elbow others politically to get what we want. Perhaps I’m ignorant to think that we can collaborate with the other side to build a brighter future. Or, perhaps I’m not, but the mere countenance of that possibility is what much of America has chosen to leave behind.

📚 What I’m reading

More important than votes. Mike Solana’s excellent post that served as much of the inspiration for this one.

Profile of Amy Coney Barrett. Barrett is Trump’s nominee to fill RBG’s seat. SCOTUSBlog did a deep dive into her background and career.

End the poisonous process of picking SCOTUS judges. A respected libertarian law professor’s proposal to depoliticize the Court.

AI policy recommendations for the next administration.

Mark in the middle. Turns out a few Facebookers have been leaking Facebook all-hands throughout the summer. When I was at Facebook, leaks were relatively rare. I think the increase in leaks is a function of increasing dissatisfaction within the company and perhaps a deterioration of the culture. In any case, the leaks are interesting gossip reading.

And finally, here’s a mesmerizing HD video of how M&Ms dissolve in water: