#39 - 🐝 Bumble S-1: How much is online dating pay-to-play?

No salt, just a quick-and-dirty financial analysis

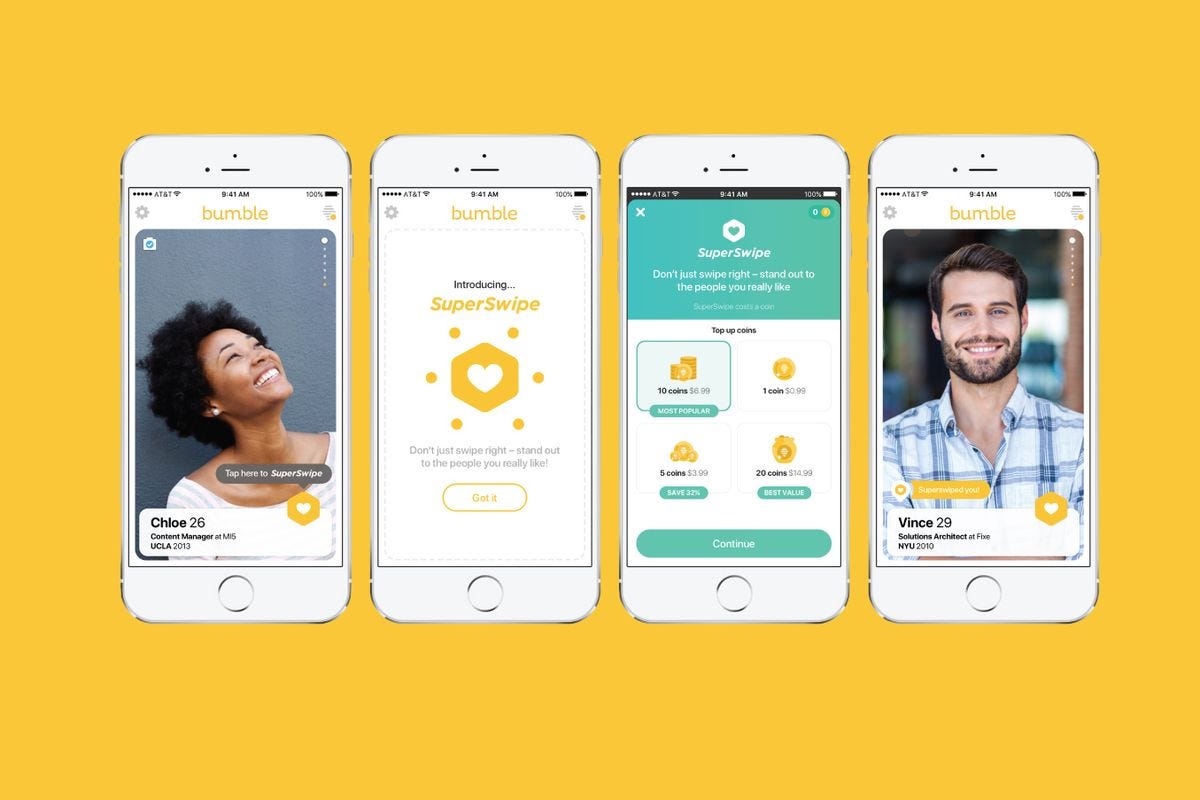

Dating apps like Bumble face a conundrum: The better a job Bumble does at matching compatible people, the more obsolete the app becomes for those people. So what might Bumble naturally do? Give people worse matches, get non-paying users to stay for a bit longer to generate more ad revenue, and fast-track the paying users to the love life they’re looking for. Bumble’s gotta make money somehow. It’s a problem of incentives.

Here’s another way to frame the problem: Bumble, as an impersonal intermediary between one person and the worldwide pool of potential mates, doesn’t have much on the line if a match doesn’t work out. To be concrete, if I swipe left on one guy out of a possible million, well, there’s 999,999 left. No skin off Bumble’s back. People have been commoditized on the Internet, anyways. Just serve me the next one. After all, Bumble is a business, so Bumble would of course love to keep me on its platform until I recoup its costs.

This is not how things worked 20 years ago (see chart below, credit: Stanford). Back then, I would probably get to know a potential mate in person, without an intermediary. Or, if there were an intermediary, that intermediary would be some trusted third-party, like a family member or a friend or a co-worker (let’s call her Alice). Alice could (probably?) only introduce me to one person at a time, and Alice has more skin in the game than Bumble, more incentives to really hit it out of the park with that one match she offers me. Indeed, a lazy match could deteriorate my trust in Alice.

So, back to Bumble. Bumble just filed its S-1 paperwork with the SEC and is set to go public soon (interestingly enough, close to Valentine’s Day) at a reported ~$6-8 billion valuation. To be honest, I found the S-1 pretty bland. Nothing really stood out to me. BUT, I read the damn thing, so I thought I’d provide a rudimentary numbers-based analysis of that pesky question above: How much has dating become pay-to-play? How much worse off are you if you don’t pay? As mentioned, dating apps like Bumble are incentivized to keep non-paying users on the platform until Bumble recoups its costs. Once non-paying users convert to paying users, however, Bumble theoretically is more willing to part with those users because they will recoup Bumble’s costs more quickly.

[Disclaimer: Of course, none of the following is investment advice, and while I’m basing a lot of my analysis on the numbers in Bumble’s S-1, a lot of numbers were absent, so I had to pull them out of thin air and make some assumptions that could be very, very wrong. I’m also conducting this analysis half-ironically, as an interesting thought experiment. What follows is also a bunch of number crunching and a level of consultant-type hand-waving, so if you don’t feel like following along, just scroll to the bottom, where I provide a tl;dr of my findings. I’ve also put together a spreadsheet with all the numbers and assumptions if you want to play around with it.]

**UPDATE**: The financial analysis below is wrong because it is predicated on an incorrect definition of Bumble Average Revenue Per Paying User (ARPPU). The correct definition of ARPPU (i.e., the one used by Bumble in its S-1) is average revenue per user per month over a given period, while my incorrect definition was average revenue per user over the total period. I’m going to leave my mistake in so you can see how I was thinking, but just know that my final numbers would change drastically if you used the correct definition of ARPPU.

Let’s start and center our analysis on the LTV:CAC ratio, the holiest of grails when evaluating pure software companies. As I wrote in Palantir goes public: Is Palantir a SaaS company?:

Because software, once it’s developed, has pretty much 0 marginal cost of distribution, the marginal cost essentially devolves into the customer acquisition cost (CAC), which, as you might guess, is one of the most important metrics for SaaS companies . . . While SaaS companies face high up-front costs, the recurring nature of revenues eventually (hopefully) kicks in and more than compensates for those initial losses, making SaaS companies the VC poster child of investments. Thus, another important SaaS metric is the customer lifetime value (LTV), the amount of revenue a customer will generate across its entire lifetime. The success of a SaaS companies depends on keeping its LTV higher than its CAC. If your LTV is higher than your CAC, then from a purely profit perspective alone, you’re incentivized to sell your software to as many people as possible, until your CAC rises to meet your LTV. VCs typically want an LTV:CAC ratio of 3:1.

Unfortunately, Bumble never gives us its LTV:CAC ratios for paid/unpaid users, so we’ll just have to come up with those numbers ourselves given what we do have. Here’s the end question we want to answer: If Bumble wants an LTV:CAC ratio of, let’s say, 2, how many months do paying users need to stay on the platform vs. how many months do non-paying users need to stay on the platform?

Here’s a list of things Bumble does tell us:

Users: Bumble has 2.4m paid users as of 9/30/2020, up 18.8% year-over-year. This means Bumble got 451,200 new paid users since 9/30/2019. Total monthly active users (including both paying and non-paying) as of 9/30/2020 is 42.1m. This means that there were 42.1m - 2.4m = ~39.7m non-paying customers.

Revenue: Total revenue for the 9 months ended 9/30/2020 is ~$416m. Average Revenue per Paying User (ARPPU), excluding any revenue generated from advertising and partnerships or affiliates, for the 9 months ended September 30, 2020 is $18.48. Revenue generated from paid users (excluding ads, partnerships, etc.) for this period is therefore $18.48 ARPPU * 2.4m paid users = ~$44m. Total revenue generated from ads, partnerships, etc. for the period is $416m - $44m = ~$372m.

Sales & Marketing (S&M): Total S&M expense for the 9 months ended 9/30/2020 is ~$115.7m.

[Assumption: As you might tell from the above, the operative range we want to be zeroing in on, given the available data, is the 9 months ended 9/30/2020. However, we don’t have that data for new user growth. We only have year-over-year user growth from 9/30/2019 to 9/30/2020. So, let’s assume that 75% of the 451,200 (= 338,400) new paid users since 9/30/2019 came from the 9 months ended 9/30/2020. In other words, 25% of the ~451,200 came on from 9/30/19 - 12/31/19.]

[Assumption: For simplicity, let’s also assume that the entirety of Bumble’s revenue came from dating.]

Average revenue per user

Using Bumble’s given information, along with some assumptions, we can arrive at an estimate for the average revenue per user per month, for both paying users and non-paying users.

Let’s start with Average Revenue Per Paying User (ARPPU). Recall that ARPPU for the 9 months ended 9/30/2020 is $18.48, but that excludes revenue generated from ads, partnerships, etc. We need to include ads and partnership revenue in order to get a picture of all the revenue that a paid user generates for Bumble. To estimate, let’s assume that the amount of ads generated by paying and non-paying users is the exact same, and recall that total revenue generated from ads, partnerships, etc., is $372m. So, for the 9 months ended 9/30/2020, the average revenue per user coming from ads is $372m / 42.1m total users = ~$8.83 in ad and partnerships revenue per user. The total ARPPU, including ads, is therefore $18.48 + $8.83 = ~$27.32 ARPPU for the 9 months ended 9/30/2020. Per month, that’s $27.32 / 9 months = $3.04/month.

We also need Average Revenue Per Non-paying User (ARPNU). Total revenue generated by paying users throughout the 9 months ended 9/30/2020 was 2.4m * $27.32 = ~$65.6m, and total revenue throughout the period was $416m, so non-paying users generated the remainder of the revenue, $416m - $65.6m = ~$351m. With 39.7m non-paying customers, the ARPNU per month is $351m / 39.7m / 9 months = ~$0.98/month.

tl;dr A paying user generates $3.04/month for Bumble. A non-paying user generates about $0.98/month for Bumble.

CAC

In broad strokes, CAC is usually calculated as Sales & Marketing (S&M) expense over a period / # new customers over that same period. Bumble doesn’t tell us how much S&M was spent on acquiring unpaid users vs. converting unpaid users to paid users. So, let’s assume that of the $115.7m S&M expense, 5% is spent on conversion to paid users and 95% is spent on acquiring new unpaid users (after all, approximately 5% of all users are paid users, and the remaining 95% are unpaid). [We also assume that no S&M is spent on miscellaneous stuff irrelevant to dating.]

Bumble also doesn’t tell us exactly how many new unpaid customers it acquired during the 9 months ended 9/30/2020. Let’s assume that of the 39.7m total non-paying customers, 20% are new.

The CAC per month for paid users, then, is $115.7m * 5% / 338,400 new paying customers / 9 months = $1.90/month. The CAC for unpaid users is $115.7m * 95% / (39.7m new non-paying customers* 20%) / 9 months = $1.54/month.

tl;dr It costs Bumble $1.90/month to convert a user from non-paying to paid. It costs Bumble $1.54/month to acquire a new non-paying user.

Finale

As stated earlier, let’s assume that Bumble wants an LTV:CAC ratio of 2 for both paid and unpaid customers. LTV = average revenue per user per month * number of months on Bumble before leaving.

To hit the LTV:CAC of 2x, paid users need to have an LTV of 1.90 * 2 = $3.80. A paid user generates $3.04 / month. Therefore, to hit the $3.80 LTV, a paid user needs to spend ~1.25 months on Bumble.

For unpaid users to hit the LTV:CAC ratio, they need to have an LTV of $1.54 * 2 = $3.08. Given that they generate $0.98 / month, they need to spend ~3.13 months on Bumble.

tl;dr A paid user only needs to spend about 1.25 months on Bumble before Bumble is okay with seeing them go. A unpaid user, on the other hand, needs to spend about 3.13 months. In other words, if you’re not paying, then all else equal, you’ll have a 2.5x harder time finding a partner. And, a cursory Google search seems to suggest that these numbers make sense.

Again, I made a ton of assumptions here, many of which may be very wrong. That said, Bumble didn’t really give me that much to work with! If you’re interested in playing with the numbers more, check out my spreadsheet here. And if you know anyone at Bumble who wants to convince me that my analysis is wrong and that Bumble reallyyy wants to help all of its customers find mates ASAP, please send this piece along 😉

📚 What I’m reading

Why the Canadian tech scene doesn’t work. (Alex Danco)

A 25-year-old bet comes due: Has tech destroyed society? In 1995, a Luddite and a tech-optimist bet on whether the tech would kill the world by 2020. Who won? (WIRED)

The need for ideological diversity in American cultural institutions. (The Volokh Conspiracy)

AI-ethics-as-a-service startups. (MIT Tech Review)

Rotten to the core? How America’s political decay accelerated during the Trump era. (Francis Fukuyama in Foreign Affairs)

Joe Biden’s letter to Dr. Eric Lander of MIT/Harvard. (Joe Biden)

Facebook has referred Trump’s suspension to its Oversight Board. Now what? (Evelyn Douek in Lawfare)

California plaintiffs sue Tencent, alleging WeChat is censoring and surveilling them. (Washington Post)

The echo chamber era. I feel like I’m linking to Matt Taibbi every week at this point, but he’s just so good. Here, he writes about the inconsistency of news media and how they manipulate headlines to get us riled up about certain threats but then silently retreat to the sidelines when those threats don’t materialize. (Matt Taibbi)

Apple’s AR headset. (Bloomberg)

Hey Christopher, appreciate your analysis and the framework!

However looking into the Annual Financial Report, I think you need to notice the ARPPU definition:

“Bumble App ARPPU,” or Bumble App Average Revenue per Paying User, is calculated based on Bumble App Revenue in any measurement period, divided by Bumble App Paying Users in such period divided by the number of months in the period.

It is a monthly average instead of whole period average.