I.

One sign of a well-functioning democratic process is that the losers accept the outcomes. If the People think that the process is rigged, then the outcome is fraudulent, and you don’t really have a Democracy.

It’s useful to think about large institutions or systems like “Democracy” in terms of processes vs. outcomes. At a certain size, when a bunch of people who don’t know/trust each other are involved in making decisions that affect the whole, you need rules to guide behavior and decision-making. As long as we agree to these processes and abide by them, we theoretically should accept the outcome, no matter how “bad” it turns out to be.

This principle plays out in various organizational contexts. For example, consider start-ups. All successful startups eventually face a scaling challenge: What happens when the start-up grows to a size where the CEO can no longer make all the important decisions? There’s a conundrum. If you’ve gotten to that size already, then obviously you’ve already done something right. But will you still be able to reproduce that “something” across all the employees, each of whom has vastly different backgrounds and priors? This is an existential question. Find a way to reproduce and scale success, or die.

The solution for the startup is to establish a uniform culture, a standardized process that guides organizational decision-making. As the company grows, the particular behaviors that resulted in success during the company’s infancy must be distilled into principles (e.g., Facebook’s famous “move fast and break things”) and promulgated throughout the entirety of the organization. Employees buy in to the culture and use it as a framework for making decisions. Even when employees are presented with problems they’ve never seen before, culture guides them to a course of action that their managers and executives would likely make if they were in the same shoes.

Consider also how our legal system works. When two private parties are negotiating a contract, they can pretty much impose any kinds of rules they want on themselves or use any heuristic for judgment to reach a resolution. But the minute those parties end up in court, courts impose a host of uniform rules of procedure that lawyers and judges have to adhere to. Why? It’s because courts adjudicate all matters of proceedings across the hundreds of millions of Americans, and in order to produce consistent decisions from judge to judge, from party to party, you need some level of standardized process in place.

Now imagine that courts don’t have any rules. The lawyers are shouting over one another. A member of the jury is the defendant’s best man. A witness is called to the stand and allowed to present hearsay evidence (“I heard her say the she saw the defendant committing the crime!”). The judge is wearing a party hat.

Without some semblance of uniformity in the rules, the nationwide court system would break down. Rulings would be unpredictable. People would lose their trust in the venerable judiciary branch of government. Would there be any sense or hope of justice left at all if our courts are completely defunct?

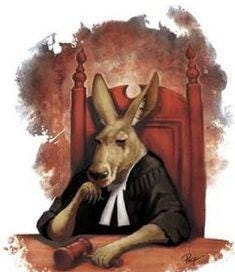

In short, processes matter when large systems make decisions. If you don’t have enough rules, or if people don’t agree on the rules, or if too many people disobey the rules, then the system breaks down. People and decisions begin splintering in every direction. Eventually, the institution loses its legitimacy. Trust crumbles. And if the institution somehow is still standing, it stands merely as a hollow shell, an outward representation of fake legitimacy that ultimately is devoid of any value on the inside. Once you’re at that point, then welcome, my friend, to kangaroo court.

II.

One popular misconception back when I was in middle school was that Wikipedia was a kangaroo court. My teachers told me that Wikipedia was a wildly unreliable source of truth or information—“never cite it for your papers.” The sentiment boiled down to: Wikipedia was so decentralized that any random person could edit any random page, and there were no rules in place for editing. Hence, kangaroo court.

Perhaps another misconception about Wikipedia is that the more polarized a topic is, the more the Wikipedia page for that topic is a kangaroo court. After all, this might make intuitive sense: If people are super polarized on a topic, then any attempts to arrive at truth on that topic could devolve into shouting matches or edit wars where one side makes a change to the Wikipedia page and the other side immediately undoes it.

It turns out, though, that Wikipedia is far from a kangaroo court, and in fact, the more polarized a topic is, the more accurate that topic’s Wikipedia page is. Wikipedia has somehow managed to create a set of rules and processes to arrive at decentralized truth—incredible!

Here’s how (emphasis mine):

Justin Knapp, a prolific Wikipedia editor with more than 2 million contributions, agrees that Wikipedia’s robust bureaucracy is crucial to cultivating a space for meaningful disagreement . . . Knapp says that even when political disagreements are fierce, or seemingly unresolvable, the clear set of editing principles — to cite facts properly, to present information in a neutral voice — allows editors to resolve disputes without devolving into toxic arguments . . . “Wikipedia has a serious collective goal and that is to create an encyclopedia,” Knapp says. “Because of the shared mission, Wikipedia editors generally have an overlap in their set of values. And these values generally override a disagreement on a particular issue.”

Put simply, Wikipedia has a strict but uniting set of rules that editors agree to and abide by. As stated elsewhere in the article, “[e]diting on contested topics is like arguing in a court of law,” not a kangaroo court.

III.

At last, here’s Twitter, in an announcement last month:

[T]oday we’re introducing Birdwatch, a pilot in the US of a new community-driven approach to help address misleading information on Twitter . . . Birdwatch allows people to identify information in Tweets they believe is misleading and write notes that provide informative context. We believe this approach has the potential to respond quickly when misleading information spreads, adding context that people trust and find valuable. Eventually we aim to make notes visible directly on Tweets for the global Twitter audience, when there is consensus from a broad and diverse set of contributors.

So… will this be a kangaroo court?

Here’s Mike Solana, glibly:

At first blush, without knowing anything more, I’m inclined to agree. If you open the floodgates all at once in an attempt to decentralize truth, you’re going to be in kangaroo court. Everyone will have weapons, and fact-checking will devolve into who is louder and who can mobilize more people in the moment.

But the product and policy people at Twitter aren’t stupid. Birdwatch is only open right now to a small test group. Twitter has already laid out values that it is asking Birdwatch contributors to abide by. Twitter has also specified a few challenges Birdwatch will need to overcome.

Even still, is this enough? In its list of Birdwatch challenges, Twitter seems to be missing what I think is its biggest challenges: In order to keep Birdwatch from turning into a kangaroo court, Twitter needs to impose and enforce strict rules (like neutrality, citations, etc.) for all Birdwatch contributors, and more importantly, contributors need to buy into those rules.

However, I’m not exactly optimistic that Twitter will be able to solve this challenge because there may be a cultural mis-match between how Twitter users use Twitter and how Twitter users will use Birdwatch. That is, if Birdwatch users habitually treat “note-taking” on Birdwatch anything like tweeting on Twitter, then we’re going to have kangaroo court. Indeed, Wikipedia has no cultural problem because it was designed from the ground up as an encyclopedia, a canonical source of truth that people can contribute to, but Twitter was designed from the ground up as a network of random 140-character (now 280) ideas that people share.

So, I’m kinda skeptical. For instance, check out some of these “notes” on Birdwatch:

Haha, this is just… not really useful? These “notes” seem like normal Tweets that I would find on my Twitter feed, not a serious attempt at providing value or reaching decentralized truth.

Anyways, when it comes to new products, businesses, whatever, it’s always easier to be a bear than a bull, a skeptic than an optimist. Birdwatch obviously only just launched, so we should suspend disbelief until we have a few more data points. At the very least, I’m happy that Twitter is willing to try a bottoms-up approach to fact-checking rather than imposing its will from the top down. But I guess only time will tell whether Twitter can keep Birdwatch from turning into kangaroo court.

📚 What I’m reading

The moments that could have accidentally ended humanity. (BBC Future)

“Mark changed the rules”: How Facebook went easy on Alex Jones and other right-wing figures. (BuzzFeed)

Shopify. (Benedict Evans)

The AI research paper was real. The ‘coauthor’ wasn’t. (WIRED)

A modest proposal for Republicans: Use the word “class.” (Astral Codex Ten)

The profound, unintended consequence of Apple’s new privacy policy. (Mobile Dev Memo)

Yuval Noah Harari: Lessons from a year of Covid. (Financial Times)

Iceberger. Okay, this isn’t really something I’m “reading,” but it’s fun and cool. (Josh Tauberer)