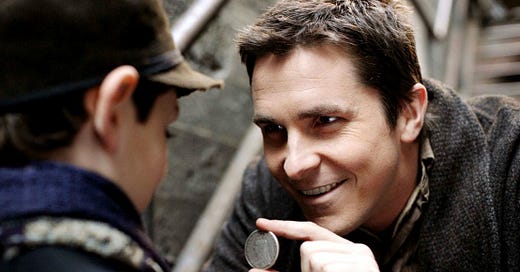

Every great magic trick consists of three parts or acts. The first part is called “The Pledge.” The magician shows you something ordinary: a deck of cards, a bird or a man. He shows you this object. Perhaps he asks you to inspect it to see if it is indeed real, unaltered, normal. But of course... it probably isn't. The second act is called “The Turn.” The magician takes the ordinary something and makes it do something extraordinary. Now you're looking for the secret... but you won't find it, because of course you're not really looking. You don't really want to know. You want to be fooled. But you wouldn't clap yet. Because making something disappear isn't enough; you have to bring it back. That's why every magic trick has a third act, the hardest part, the part we call “The Prestige.”

[Note: If you haven’t watched The Prestige yet, I highly recommend it — or, at the very least, watch the trailer!]

I.

When it comes to magic, we want to be fooled. We know there’s a trick somewhere, and search desperately as we may for the trick, the more we are fooled, the better. By shining a light on the trick, the magic is ruined.

I’d argue that something similar exists in the world of venture capital. Here’s Matt Levine:

What you want, when you invest in a startup, is a founder who combines (1) an insanely ambitious vision with (2) a clear-eyed plan to make it come true and (3) the ability to make people believe in the vision now. “We’ll tinker with hydrogen for a while and maybe in a decade or so a fuel-cell-powered truck will come out of it”: True, yes, but a bad pitch. The pitch is, like, you put your arm around the shoulder of an investor, you gesture sweepingly into the distance, you close your eyes, she closes her eyes, and you say in mellifluous tones: “Can’t you see the trucks rolling off the assembly line right now? Aren’t they beautiful? So clean and efficient, look at how nicely they drive, look at all those components, all built in-house, aren’t they amazing? Here, hold out your hand, you can touch the truck right now. Let’s go for a drive.” That’s not true, but it’s a nice metaphor; the goal is to get the investor to see the future, so she’ll give you money today, so that you can build the future tomorrow. [ . . . ]

Startup investors understand that this is the game they are playing; they want to be sold an enthusiastic vision of the future by someone who believes it so purely and tangibly that he thinks it has already happened. Sometimes it works out great, the founder achieves his vision, the future is as predicted and the investors get rich. Other times—most times—it doesn’t work out, the vision fails, the future is different and the investors lose their money. It’s fine. That is the game they are in, betting on wild visions of the future sold to them by wild visionaries; only some of them have to come true for the investors to get rich.

To make the analogy more concrete, the entrepreneur is the magician, and the venture capitalists are the audience members, inspecting the entrepreneur’s act to find the trick but nevertheless hoping to be dazzled.

II.

Let’s frame venture capital explicitly in terms of the three steps of magic mentioned in The Prestige.

The Pledge is the entrepreneur’s visionary pitch to the investor. As an initial matter, is this market big enough to make venture capital returns? What are the existing solutions to the problems? And what is the entrepreneur’s specific solution to the problem? What is his vision for the future?

The Turn is when the entrepeneur’s pitch is so dazzling that, in spite of the investor’s due diligence, she still excitedly cuts a check. The entrepreneur shows off everything his company has accomplished to the current moment, a bunch evidence that the he has already done something extraordinary and magical in the problem space. The investor is asking for the entrepreneur’s references and doing financial modeling on where the entrepreneur’s company is heading. She’s looking for the trick, for all of the reasons why this company might fail, but if she concludes that this is unicorn magic, she cuts a check. Most startups, however, don’t make it from The Pledge to The Turn. Famed VC firm a16z, for instance, apparently hears 3,000 company pitches per year but only invests in 20 of those companies.

But the investor doesn’t stand up to clap yet, nor does the entrepreneur, because the hardest part has yet to happen: The Prestige. If The Turn is about showing off everything that happened before the check was cut, The Prestige is about everything that happens afterwards. The Prestige requires the entrepreneur to grow the company, meet and exceed financial projections, and eventually not only return money to the venture capitalist, but also change the world in the way the entrepreneur had envisioned during The Pledge. And this is where the magic analogy begins to break down: When a company successfully performs The Prestige, the magic is no longer magic—it’s been turned into a reality. There’s no more “trick” that everyone’s radically skeptical about, no more veil that people are trying to pierce. Many companies don’t make it from The Turn to The Prestige. Famously (infamously?), venture capital investments adhere to a power law. A teeny-tiny minority of companies generate the vast majority of returns. It wouldn’t be surprising, for instance, to see a return profile like the following for ten investments: five return 0x, two return 1x, two return 2-3x, and one returns 10x.

III.

One interesting way to think about a private company going public is that it lets retail investors behind the curtain to get in on the magic of a startup… Except not exactly. Traditionally, by the time a company goes public, The Prestige has already happened. The venture capitalists are already giving the standing ovation. The startup has already found a way to generate sustainable revenues (and perhaps even profits). The startup already has a product with strong traction. The runway for the startup has already been sufficiently de-risked to allow participation from the public. Indeed, going public is the imprimatur of sustainable success. The opaque magic act in the world of early-stage venture capital can now give way to the highly institutionalized, transparent, and scrutinized world of public markets.

A couple of years ago, the trend was for high-growth unicorn tech companies to stay longer and longer in the private markets. Rather than going public, they would raise increasingly large “growth equity” or late-stage VC rounds. And this made sense to me! Visionary founders don’t want to have their businesses put under a microscope. They don’t want to bend to the will of public markets. There’s still magic yet to perform. Wait for The Prestige before you applaud.

Interestingly, we’re now seeing SPACs reverse this dynamic. Rather than raising later and larger VC rounds, high-tech growth companies are entering the public markets sooner through a SPAC acquisition. The public can actually get in on the magic sooner. Of course, there are some great benefits to going public sooner. A public company has easier access to future capital. Rather than raising successive rounds from venture capitalists (which can be very cumbersome!), a late-stage private company can just raise all that money at once through a SPAC. By going public a company also provides liquidity for its investors and employees. And going public is also a form of advertising, giving the company more prestige among shareholders, customers, and analysts. This is especially true if the company is going public via SPAC where the SPAC sponsor is a celebrity like Chamath Palihapitiya or Bill Ackman.

But what if companies are getting SPAC’d before The Prestige has yet to happen?

IV.

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

The tech closest to actual magic is what’s called “deep tech.” Deep tech involves risky (and often literally) moonshot ideas, super high capital expenditures, lengthy sales cycles, and highly proprietary technology. Examples of deep tech ideas include manufacturing organs in space, delivering people around in drones, and genetically engineering blue fin tuna. Unlike traditional software investing, deep tech investing hardly has any sort of uniform playbook, timeline, or metric for success. It’s much more difficult to evaluate deep tech companies because much of their worth is tied up in future revenue generation opportunities rather than existing revenue.

Recently, we’ve seen an increasing trend towards more deep tech companies getting SPAC’d. This in and of itself is not inherently a bad thing, but what I find slightly concerning is that a few of these companies haven’t made a single cent in revenue. Nikola, an electric truck company that got SPAC’d in June 2020, soared to a $34bn valuation despite making $0 in revenue. It has also recently been embroiled in allegations of financial fraud. Virgin Galactic, a company that promises to take civilians on space tourism trips, got SPAC’d in October 2019 without having sent a single tourist to space yet. Virgin Galactic’s lackluster 2020 Q4 earnings call revealed that it’s continuing to push back plans for its test flights. And Joby Aviation, a passenger drone company, recently got SPAC’d in late February but won’t be ready to start shuttling people around until 2024. Don’t get me wrong, companies like Joby are extremely cool, but there’s still a lot of magic that needs to happen in the intervening years.

So why are SPACs targeting these sorts of companies to go public?

S-1s prohibit companies from including financial forecasts. SPACs, on the other hand, don’t need to file S-1s and in fact are governed pretty much exclusively under merger & acquisition law. SPACs use a private due diligence process which allows companies to present financial forecasts and promote themselves heavily before the SPAC transaction. This presents a unique opportunity for SPACs to merge with more vision-driven or high-growth earlier stage companies, where the trailing financial profile is not representative of the company’s trajectory.

Over the past year or two, we’ve seen an increasing public fascination with growth stocks. Many SPAC’d companies like Joby Aviation are exciting, high-growth businesses. This fits the social-financial milieu, appealing heavily to the unshackled public of retail WSB / Robinhood investors.

Venture capital investors who disagree with me will argue that many of these companies have already performed The Prestige, so what’s all the fuss about? Companies with differentiated technologies, strong management teams, and full order books may still be good businesses, even if these companies are years away from generating revenue.

V.

Should the public be allowed to invest in pre-revenue deep tech SPAC’d companies?

My guess is that your view on this question will depend on whether you think the Gamestop frenzy was a good thing or not. I’ve previously written my Gamestop take here.

On one hand, I’m in favor of democratizing finance from the hands of a few institutional incumbents to the People. SPACs do exactly this, whether or not companies still have to perform The Prestige. Specifically, SPACs democratize finance from the hands of late-stage venture capitalists and investment bankers to retail investors. To clutch my pearls and say that it’s unsafe for retail investors to trade stocks seems a bit paternalistic (“you’ll hurt yourself, kid!!!”), and a small libertarian voice in my head tells me that retail investors should be allowed to live and die by their own sword.

The obvious pushback here is that many securities laws are designed to protect retail investors. In fact, a bunch of laws are designed to protect us from ourselves (seat belts, cigarettes, etc.), and even if you call these laws paternalistic, that doesn’t necessarily make them bad, at least from a utilitarian perspective.

I think these are fair points. I’d obviously prefer for every company that gets SPAC’d to be a great company. I’d also prefer that retail investors aren’t goaded into SPAC’d companies yet left unknowingly holding the bag if these companies turn out to be trash. And if there’s a way to do these things without imposing super heavy regulations on SPACs, I’m all for it. I dunno’, you can imagine something like a big red box on Robinhood every time you want to buy shares of a SPAC saying “This company just got SPAC’d and has never made a single cent in revenue, you should be careful.” And if the retail investor still goes through with it, then so be it. That seems to be a pretty lightweight requirement. However, I’m worried that heavy-handed regulations (like deal-structuring or disclosure requirements) might reduce not only the number of bad companies to get SPAC’d but inadvertently also the potential number of good ones too. Indeed, heavy regulations might defeat one of the purposes of SPACs, which is that they’re far less cumbersome than the traditional IPO process.

VI.

Some people claim we’re in a SPAC bubble. In the month of January, nearly 100 SPACs raised nearly $26 billion. We’re living through a time where capital is chasing startups, rather than the other way around. I bet a lot of this capital will find great companies that are “ready” to be taken public, but I also bet that some of this desperate capital may find its way to companies that are years away from completing The Prestige. Would you consider this a bubble? Or a sustainable trend? The answer to these questions will depend on how well the public market adapts to these types of companies that are based entirely on future projections and growth rather than current revenues and profitability. While public markets traditionally have not been patient, maybe we’re living through a fundamental shift in the behavior of public markets thanks to the flood of WallStreetBets investors. I honestly have no idea. Traditional history suggests that we’re witnessing a frothy bubble, but as I’ve written previously, much of tech is fundamentally different from what came before.

📚 What I’m reading

Private schools have become truly obscene. (The Atlantic)

How Neopets predicted the future of the social Internet. (The Ringer)

Ten breakthrough technologies 2021. (MIT Technology Review)

Consumer technology trends 2021. (Heartcore)

Technology, freedom of speech, and Rush Limbaugh. (Francis Fukuyama in American Purpose)

As remote work becomes the norm, vast new possibilities open for autistic people. (Wall Street Journal)

Interview with Martin Gurri. (Matt Taibbi)

Criticizing public figures, including influential journalists, is not harassment or abuse. (Glenn Greenwald)

Trapped priors as a basic problem of rationality. (Astral Codex Ten)

And finally, given this week’s focus on magic, here’s Eric Chien’s amazing “Imagination Coins” routine again (it’s just so clean):