Administrative note: I’m going to be taking a break from writing for a bit.

I.

Last week, I analogized entrepreneurship to a magic act: The entrepreneur is the magician, and the venture capitalists are the audience members, inspecting the entrepreneur’s act to find the trick but nevertheless hoping to be dazzled.

I also framed this in terms of The Pledge, The Turn, and The Prestige (from the famous movie The Prestige):

The Pledge is the entrepreneur’s visionary pitch to the investor . . .

The Turn is when the entrepeneur’s pitch is so dazzling that, in spite of the investor’s due diligence, she still excitedly cuts a check . . .

But the investor doesn’t stand up to clap yet, nor does the entrepreneur, because the hardest part has yet to happen: The Prestige . . . The Prestige requires the entrepreneur to grow the company, meet and exceed financial projections, and eventually not only return money to the venture capitalist, but also change the world in the way the entrepreneur had envisioned during The Pledge.

I framed (1) The Pledge, (2) The Turn, and (3) The Prestige from the point of view of the entrepreneur, but it turns out that we can assess these three functions from the point of view of the investor as well. VC firms need to do these three things well in order to be successful:

(1) Deal flow: VC firms need to have a constant stream of companies at the top of the funnel. Using the magic analogy, they need to be hustling to get tickets to as many shows as possible.

(2) Picking: VCs need to know what companies to pick and what companies to walk away from.

(3) Support: After picking a company, VCs need to provide support to help the company grow and accomplish The Prestige. For example, does the VC firm have a wide network that the company can plug into? Does the firm have some sort of expertise in a particular area (e.g., regulatory issues, hardware expertise, etc.)?

[Note: The fourth function the VC needs to do well is winning the deal, which happens in between picking and support. I’ll try to discuss this in another post sometime.]

II.

The stereotypical VC is the singular visionary who excels at the picking function. She thinks futuristically, pondering what the world will look like ten years from now and how a startup could bring that future to fruition. She has strong convictions but at the same time is willing to suspend disbelief of outlandish ideas. The paragon VC can identify diamonds in the rough that everyone else, even other VCs, pass over. In short, she is an iconoclast.

However, I wonder if the picking function is getting easier, if the iconoclastic VC is in shorter and shorter supply (or even non-existent). Venture capital has been around for quite a while now, and a lot of ink has been spilled on how to identify superstar companies. For example, consumer apps with product-market fit are supposed to see their user numbers skyrocket, at something like > 100% growth per year for the first few years. Strong SaaS companies are supposed to triple their annual revenue, then triple, double, double, and double it again (called “T2D3”). Because the strength of a SaaS company is relatively easy to ascertain, VC firm Tribe Capital has even quasi-automated the picking function for SaaS companies with its Magic 8-Ball software.

To be fair, I’m not super confident in saying that picking has become drastically easier. Different companies are different, and there is no strict mold for success—if a SaaS company grow revenues by 150% instead of 200%, a venture firm probably isn’t going to immediately write it off... Moreover, people might ask why, if picking really were that much easier, do venture returns still adhere to power laws? Why don’t we see a higher proportion of winners among an investment portfolio?

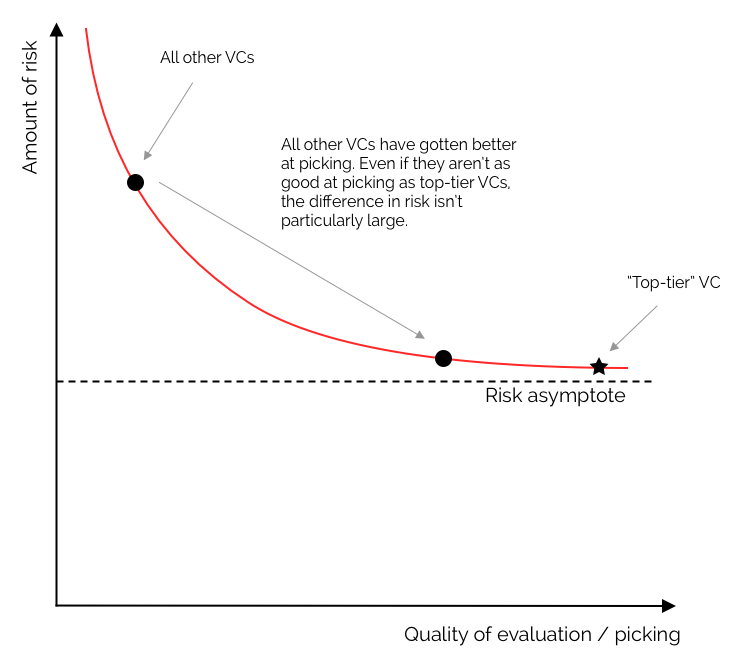

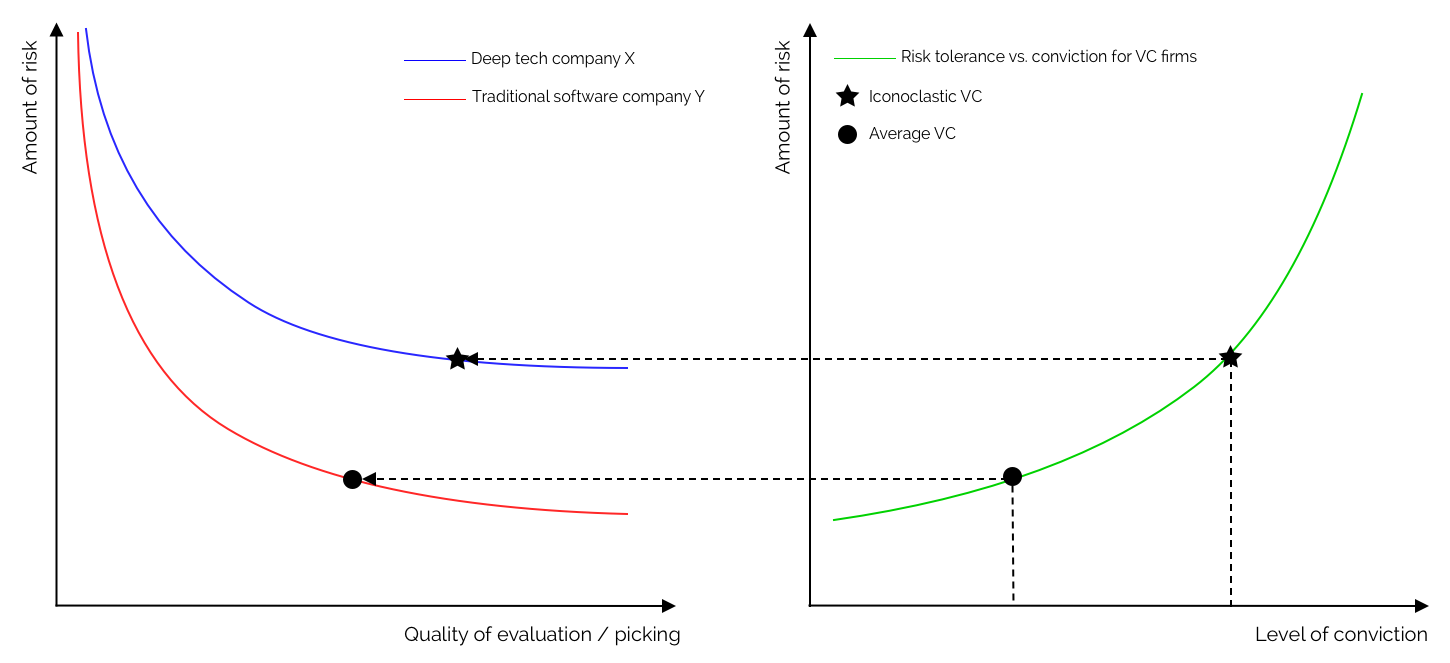

My point is not that picking has become easy on an absolute basis. Investing in startups, especially at the early-stage, is still really risky (ahem, startups still have to complete The Prestige). Rather, my point is merely that there are ballpark markers for future success (e.g., user growth, revenue growth, employee growth, founder quality, etc.) that will de-risk an investment to a certain point, and many VC firms know to diligence these markers when thinking about an investment opportunity. Perhaps you can get the investment risk down to an asymptotic value, but the continuing existence of high amounts of risk and VC power laws doesn’t automatically mean that picking hasn’t gotten at least relatively easier.

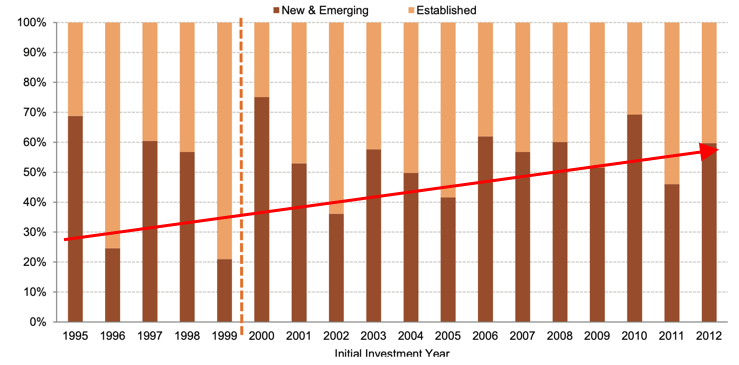

If my hypothesis is correct, that picking has gotten a bit easier, then perhaps what we’d really expect to see is more VCs getting on unicorn deals (rather than only the “best” VCs being uniquely able to identify the unicorns). And indeed, this seems to be what we’re seeing. According to a 2014 report by Cambridge Associates, from 2000 through 2012, 70 VC firms registered at least one “top 10” deal (based on return), and no firm accounted for more than 7.7% of the top 10 deals across the period. In contrast, during the pre-2000 period, only 25 firms had at least one top 10 deal, and five firms accounted for at least 8% of all the top 10 deals in the period. Moreover, as shown in the Figure below, more and more of the value in the “top 100” investments (based on return) is being captured by new and emerging venture funds. This all lends some credence to the idea that picking is, indeed, getting a bit easier.

III.

I’ve spoken to a few of my friends who’ve founded companies. Many don’t have positive conceptions of VCs, in no small part because they think VCs aren’t the iconoclastic visionaries they’re made out to be. And this makes sense—with so much capital in the ecosystem today, and with so many VCs having studied the home-run VC exits, you have a proliferation of VC firms that don’t need to be iconoclasts in order to earn strong returns.

But I don’t think this means the iconoclast VC investor is a myth. Some VCs proactively craft theses / roadmaps about particular markets and doggedly chase startups that match their vision of the future. It’s all very forward-thinking. Bessemer, for instance, tends to do this quite well. Other VCs like Lux Capital make a conscious decision to invest in industries or technologies that most other VCs tend to shy away from. For example, while B2B SaaS is flush with capital, deep tech hardware attracts very few VCs because, as discussed last week, deep tech is way riskier. Because there is less of a uniform playbook for deep tech investing, many VC firms are scared away, thinking the risk is too high, no matter how much due diligence they conduct (see Figure below). Iconoclastic VC firms, though, often come up with their own playbooks for the future of deep tech and have sufficient levels of conviction to make an investment, notwithstanding the risk.

📚 What I’m reading

Late-stage pandemic is messing with your brain. (The Atlantic)

The robots are coming for Phil in accounting. (New York Times)

U.S. to impose sweeping rule aimed at China technology threats.

The Biden administration plans to let the Trump-era rule on technology purchases and deals take effect, despite U.S. business objections about its scope. (Wall Street Journal)How Dapper Labs scored NBA crypto millions. (Protocol)

A year of secrets. COVID-era confessions, from ski trips to lovers to second jobs. (The Cut)

Scientists developed a clever way to detect deepfakes by analyzing light reflections in the eyes. 🤯 (The Next Web)

Moore’s Law for everything. (Sam Altman)

The end of Silicon Valley as we know it? (Tim O’Reilly)

What we learned about Clearview AI and its secretive ‘co-founder.’ (New York Times)

MOOCs failed, short courses won. A brief look at Coursera’s upcoming IPO. (Inside Higher Ed)