#25 - Facebook bans QAnon

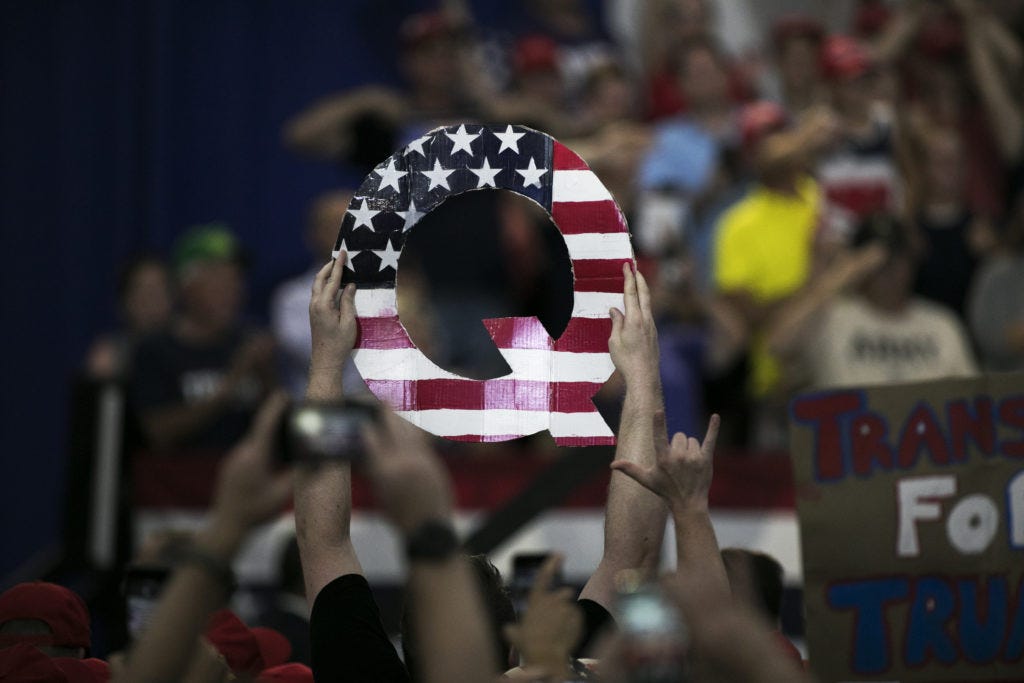

If you don’t know what QAnon is, I highly suggest you check out this piece from The Atlantic about the conspiracy group. In short, QAnon is a far-right fringe group that believes Donald Trump is a messianic figure working to oust Satan-worshiping pedophiles running a global child sex-trafficking ring. The FBI warned last year that the group was becoming a domestic terrorism threat (check out Business Insider’s compilation of crimes committed by QAnon members), and Facebook, earlier this week, made the decision to ban all QAnon content from the platform, labeling the conspiracy group a “militarized social movement.”

First of all, let me say that as a narrow matter of policy, I think QAnon is a huge hoax, I’m happy that Facebook banned it, and I’d be so happy to see its membership go to 0.

But the tension for me comes as a broad matter of principles. I have a really hard time reasoning about whether Facebook banning QAnon is something I should agree with ideologically and whether there is a better way for private companies to exercise their power over Internet speech. My logic in the following analysis is muddled at best, but I’m trying my hardest to make sense of what I actually believe.

Protecting ideas

Minority (and dare I say fringe) ideas need to be afforded at least some level of protection. Here’s Peter Thiel:

[A]s a democracy, we think if 51% of people believe something, they’re probably right. If 70 to 80% believe something, it’s almost more certainly right. But if you have 99.99% of the people believe something, at some point, you shifted from democratic truth to North Korean insanity. And so there’s a subtle tipping point where the wisdom of crowds shifts into something that’s sort of softly totalitarian.

Say what you will about Peter Thiel generally, but I think he has a point here. When it comes to sociopolitical issues, there’s hardly ever a “right” answer. So, I tend to be initially skeptical of dominant views (as I’ve previously described here) until I’ve done proper research on those views. If I were to plot my level of skepticism against the “mainstream-ness” of these sociopolitical issues, it’d probably look something like this:

But this begs the question: Where do we draw the line for protecting minority ideas? You might respond that QAnon has crossed that line for protection, in which case I’d agree but then repeat the question: Where, exactly, is that line? Violence or hate speech seem like good places to draw that line. But then: What, exactly, constitutes violence, and what constitutes hate speech? There’s a definitional problem here.

If an amorphous term were included in a federal law, Congress would probably try to include a legal definition for those terms. If further ambiguities exist, the public sphere would deal with these ambiguities through the courts. Courts interpret the law, and through years and years of litigation over the terms of a law, the public can have a good grasp on what might cross the line and what might not. In the private sphere, however, companies traditionally draw the line wherever they’d like, behind closed doors that the public can’t access.

Furthermore, in the public sphere, if you don’t like a law, you can call your representative or senator and drum up support to change the law. Alternatively, you can vote politicians out of office. We have elections every so often to, in a way, force turnover, in case the People aren’t happy with what they have. But for private companies? We don’t have anything of the sort. If companies adopt policies we agree with, then great! But what if companies don’t? For instance, imagine an alternate universe where Mark Zuckerberg and a bunch of the tech executives are now staunchly conservative. The tech companies could declare that groups on the left (like “Antifa” or even “Black Lives Matter”) are “related” to some recent real-world incidents of arson or anti-police violence. The companies would be perfectly (and legally!) free to draw the line at these groups.

I often engage in this sort of counterfactual thought experiment to see if I agree with the manner in which big tech exercises power, or whether I merely agree with the direction. Put differently, in these alternate realities, I would certainly take issue, on a policy level, with where a company chooses to draw the line for banning content. But on a principles level, a level that is invariant to the particular policy implementation, I have some issues: First, there’s an incredible level of opacity into how companies draw and enforce the line (in other words, how companies solve the definitional problem). Second, and even worse, if you happen to cross that line, or if you happen to dislike where a company drew the line, there’s … really nothing you can do about it. Sure, maybe you can delete the social media app, but that’s kinda’ like shooting yourself in the foot, given that so much online discourse is consolidated in a few apps. Maybe you can take your ideas to the dark web in a corner of the Internet, but if your goal is to start a social movement, you’re effectively handicapped because of the friction in accessing the dark web. Your best bet is to organize some sort of collective action (e.g., boycott ads) to hold the platform accountable until it changes some of its policies, but even that isn’t guaranteed to produce change.

This all brings me back to the idea of the corporate nation-state I discussed last week. America was founded on the freedoms of speech and expression, and while these freedoms protect us from government interference, the line between private and public has been getting blurrier. For example, politicians are repeatedly dragging the major platforms left and right to testify on Capitol Hill, and many platforms are working with the governments and law enforcement to identify dangerous content. In addition, courts have declared that Twitter can’t permit President Trump to block his critics on the platform because that would violate the First Amendment. Twitter is recognized by the law as a de facto political channel. Or, if you will, a public square that is slowly migrating onto private land. We have to acknowledge that, on the whole, a small handful of social media sites have control over national political discourse and more broadly, speech and expression on the Internet, and that power must be exercised carefully.

Of course, describing the problem is always easier than finding a solution. In broad strokes, though, here are a few ideas:

Increased competition in the social media space so that if you are silenced unfairly by one, you can take your ideas elsewhere while still being able to compete in the marketplace of ideas.

Increased ex post process for individuals and groups who have been blocked or silenced. Facebook is doing this with its Supreme Court for content moderation. Third-party neutral arbiters would determine whether content was rightly or wrongly banned from a platform, according to the platform’s own content moderation rules.

Increased ex ante process when making changes to content moderation policies. Perhaps companies can borrow something from administrative law, whereby public agencies issue “notices of proposed rule-making” every time they make a new rule. This “NPRM” invites public comments to ensure that its new rules are serving the people. Of course, this is costly to administer and can slow the speed of innovation.

Marketplace of ideas redux

The QAnon ban also made me wonder how QAnon became so popular in the first place. Part of the answer, I think, lies in a failure in the marketplace of ideas, and I wonder how (or even if) companies might be able to fix this failure.

To illustrate the marketplace of ideas, I’ve often quoted this judicial opinion written by Justice Kennedy of the Supreme Court:

“The remedy for speech that is false is speech that is true. This is the ordinary course in a free society. The response to the unreasoned is the rational; to the uninformed, the enlightened; to the straightout lie, the simple truth . . . The theory of our Constitution is ‘that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market’ . . . Only a weak society needs government protection or intervention before it pursues its resolve to preserve the truth. Truth needs neither handcuffs nor a badge for its vindication.”

In other words, as I’ve previously described this marketplace of ideas:

The marketplace of ideas suggests actually that we ourselves are our own arbiters of truth. We digest the multitude of information coming our way, and we arrive at our own ultimate conclusions about what to believe, based on the merits of what we see. As information competes in a “survival of the truthiest,” the “truth” organically emerges as our clear winner. Or, at least that’s what’s supposed to happen in theory.

In that post, I emphasized that the marketplace of ideas doesn’t function exactly as we’d like because we are inundated with information, and we necessarily rely on imperfect proxies to separate the wheat from the chaff.

Here, I’ll describe another way that the marketplace of ideas has broken down. Namely, individuals are intelligent, but crowds are dumb. In a commons, the primitive part of our brain takes over, and we have a harder time assessing truth.

In 2017, a few researchers studied why and how people tend to believe in conspiracy theories, and their findings illustrate this truth about crowds. Specifically, people have a longing for control and coherency, but we often feel isolated, helpless, and unable to make sense of the world. As a result, we accept these group conspiracy theories in an attempt to weave a narrative through the immense ambiguities and to build connection among an in-group by blaming negative outcomes on others. In other words, someone who buys into a conspiracy theory sacrifices accuracy in return for certainty and belonging.

The Internet compounds this problem. Of course, in the pre-Internet world, conspiracy theorists still existed, but in that world, the community of conspiracy theorists couldn’t really find one another and influence others en masse. On the Internet, however, fringe groups can easily discover each other and amplify their voices using Facebook and Twitter as megaphones. These crowds only grow bigger and louder over time, not thanks to any inherent merit in their ideas, but thanks to the fact that their radical ideas can take advantage of a worldwide audience of unassuming minds.

The Internet has coopted the marketplace of ideas, increased our susceptibility to groupthink, and compromised our ability to think independently. Many free-speech absolutists think of this freedom in intellectual terms, like philosophers having a reasonable discussion. But it's not that. On the Internet, it’s more like monkeys with all brainstem and no cerebral cortex.

📚 What I’m reading

How the domestic aesthetics of Instagram repackage QAnon for the masses. QAnon misinformation is completely blending in with other posts on Instagram. Users are packaging and presenting the fringe theory alongside hearts, moms, and beauty brands. This trend is leading to increased visibility / growth at the top of the funnel and, even worse, normalization of the dangerous idea. “It’s a huge misconception that disinformation and conspiracy theorizing happens only in fringe spaces, or dark corners of the internet. So much of this content is being disseminated by super popular accounts with absolutely mainstream aesthetics.” I believe in bringing misinformation to light, but what happens when you can’t detect it? Or worse, what happens if it’s already in front of your very eyes?

Why did Facebook ban QAnon now? Casey Newton provides his take on the Facebook QAnon ban.

Brian Armstrong’s follow-up. Apparently, 60 employees have left Coinbase after Brian Armstrong’s memo essentially forbidding politics from the workplace. I wrote about this last week.

Americans increasingly believe violence is justified if the other side wins. Trump has made it pretty clear that he’s not going to go quietly away into the night if he loses the election. It looks like some of the left is also willing to endorse violence if Biden loses. Overall, I’m scared for the next 3 months of our country.

COVID-19 is accelerating an unfair future. I find it kind of strange that President Trump tweeted that the virus is nothing to worry about when he got the best care in the nation, paid for by taxpayers. Meanwhile, many people are suffering from the virus because they can’t afford even a fraction of the care that Trump got. The article also notes how minorities are suffering (e.g., dying, losing jobs, etc.,) disproportionately from COVID-19.

Republic senator puts democracy lower on his ladder of values. This is extremely interesting to think about. On a philosophical level, yes, the goal of government is to ensure the happiness and welfare of its people. However, America is founded on the principle that democracy is the most effective (least bad?) way to do that.

China is winning the war for global tech dominance.

And finally, here’s a video I watch at least multiple times per month.