Friends, it’s been a long time. Things have gotten busy, but I’ve been publishing other writings elsewhere in the meantime. If you’d like to read some of it:

I co-authored an AI policy paper with Stanford’s Institute for Human-Centered AI. The full report is here, but you can read an op-ed we wrote for The Hill here.

I analyzed the future of work with my friend Andy Ku. You can read that here.

At this point, my Substack writing experiment can no longer appropriately be called a “newsletter,” and I sadly can’t make any promises on any frequency with which I’ll write moving forward. Nonetheless, I’ll still try to write when I have ideas and time, and I hope you’ll continue to support me.

Happy 2022,

—Chris

I.

Something happened to America in the 1970s that we haven’t quite recovered from.

Real wages have been stagnant, income inequality has exploded, inflation has run amok, we’ve been staring further and further down the twin barrels of both the largest federal debt and the largest trade deficit in history, politics has become increasingly polarized, etc. The aptly-named website wtfhappenedin1971 can blast you with a firehouse of data if you want more evidence illustrating the strangeness of our most recent chapter in American history.

What happened to us? One theory is that the ‘70s were simply an organic extension of the ‘60s, but I don’t think this is correct. To be fair, the ‘60s had their dark moments. Social chaos? Sure. Many violent riots. Assassinations of JFK and Robert Kennedy, MLK Jr. and Malcolm X. And yes, failures too. We botched the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the Bay of Pigs was a disaster. Our entrance into the Vietnam War would prove incredibly costly and, ultimately, a stain on our history.

Notwithstanding our failures, though, the ‘60s held revolutionary promise. Amidst the chaos, people came together. Things were happening. There was a sense of progress. The civil rights movement crested, and activists actually got politicians to get things done in the landmark Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts. With Woodstock and the Summer of Love, millions of youthful, idealist boomer-hippies united, believing in something more and celebrating peace, love, ecology, natural foods, meditation, animal rights, and the Beatles. We finally capped off the decade by putting man on the moon, unshackling humanity from our blue marble. The Apollo 11 moon landing brought us together in front of our bulky boxed televisions to share a breathless moment, and as the 1960s came to a close, it seemed like we were just opening a new frontier, a new limitless future, rich with cultural, social, political, economic, and technological progress.

But the existence of a frontier doesn’t mean it will become a destination, much less that we will get there. What happened in the 1970s that caused the frontier to close off?

II. Governmental decline

Venture capitalist Katherine Boyle believes that things changed when we ended the draft in 1973. Prior to the ‘70s, we were proud to serve our country in the military and government. Washington had always attracted the best and brightest young graduates, but when the draft ended, top talent began going elsewhere.

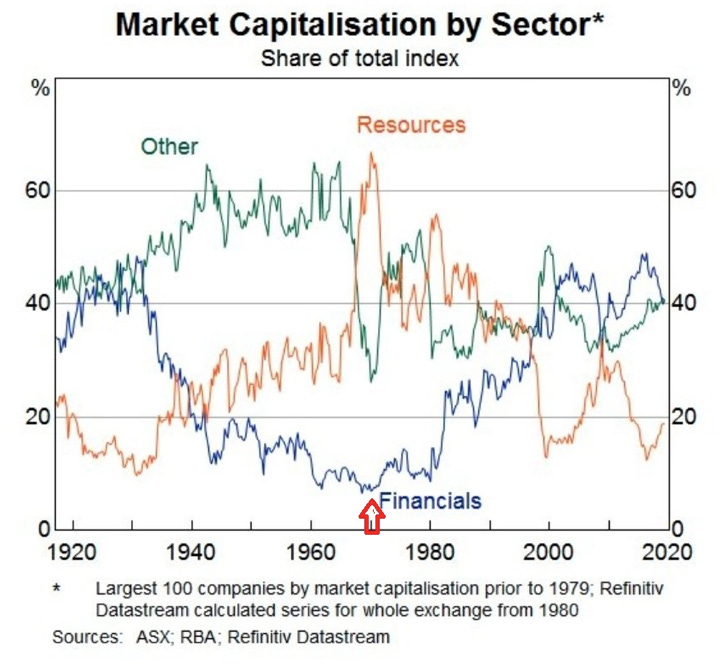

You can already guess where they went instead: Finance. The financialization of the economy began in earnest starting in the 1970s (see below), and Ivy League graduates increasingly shirked government for banking, consulting, and private equity. Then in the 2010s, Boyle notes that the tide shifted again towards tech. The net result has been a massive brain drain from DC.

It doesn’t help that we also lost faith in our government in the ‘70s, further contributing to government sclerosis. In 1971, the Pentagon Papers were leaked by the New York Times and The Washington Post: The federal government had been lying to us about the state of the war in Vietnam, telling us that we were far more successful than we actually were. In reality, too many of our young men were dying, and no progress was being made. Nixon embarrassingly withdrew our troops in 1973, and John Musgrave, a Vietnam vet, aptly summarized the prevailing attitude of the day: “We were probably the last kids of any generation that actually believed our government would never lie to us.” Indeed, shortly after our withdrawal from Vietnam, the Watergate scandal broke, only widening the rift of distrust between the people and the American government.

As a result of the brain drain and cynicism, we just can’t get anything done anymore in DC. Boyle argues that, instead, America today is de facto governed by a “shadow capital” in Silicon Valley, by optimistic technologists that essentially have more influence on progress and policy than do the policymakers themselves. For example, space launch, which was the triumph of American government, academia, and industry in the 1960s, is now firmly in the hands of industry. The last Apollo mission to the moon took off in 1972, and NASA fully closed its doors to space launch in 2011. Supersonic transport, another wild-eyed idea, also receded from the government consciousness. Government funding for this futuristic technology was fully withdrawn in 1971, and it wasn’t until 50 years later—the present day—that private companies would re-explore the promise of American supersonic travel. And of course, software. The narrow cone of industry progress in software technology has been one of the few shining spots to American dynamism since the 1970s. But the government infamously sucks at writing its own software, as I’ve written about previously.

III. An obsession with globalization

Peter Thiel characterizes the post-WWII era as a period of 0 → 1 innovation (“technology”), and the ‘70s and beyond as a period of 1 → N innovation (“globalization”). In other words, we actually used to build new things as a country,1 but starting in the ‘70s, we began focusing instead on spreading existing innovation across the world, leading to American stagnation.

I find Thiel’s argument compelling, but it lacks connective tissue. He starts with the premise that globalization began again in the 1970s, but he then seems to make the logical leap that the start of the globalization engine in the ‘70s came at the expense of technological development—why? Thiel himself even admits that there were periods of time where we witnessed both globalization and technological development concurrently. So was there something unique about the 1970s such that the emphasis on globalization was correlative with stagnation?

To be fair, it’s possible that no connective tissue is needed at all, that the rise of globalization need not have explanatory power for the decline in technological innovation.2 After all, Thiel has been outspoken and incisive in detailing other reasons (e.g., regulatory failure) for technological stagnation. However, I’ll make a feeble attempt to draw a line between globalization and stagnation, focusing on the loss of the American labor identity.

Let’s start with the globalization premise. The 1970s indeed marked a significant step change towards increasing globalization, a change so stark that it seemed to be a clean breaking point from the past. The elephant in the room is, of course, China. In 1971, “ping pong diplomacy” began, and Henry Kissinger made his famed secret visit to China. After years of being closed, China once again re-opened its doors to the West, marking the beginning of a multi-decade economic miracle, facilitated in part by the U.S.

But let’s not focus on China to the exclusion of other countries.3 In 1971, the American trade balance flipped negative for the first time in the century, largely driven by trade deficits with our allies in Europe and Japan. “Free trade was no longer free nor trade,” the American Federation of Labor declared at the time. Indeed, American diplomats accepted our allies’ severe restrictions on U.S. imports while simultaneously allowing them to develop vibrant export-oriented economies that flooded our markets. Democratic Senator Abraham Ribicoff sounded the alarm bells in 1971 when he decried our allies’ “aggressive” trade policies as having “disregard for basic American economic interests,” but America continued to tolerate them even as the global economy tanked in the mid-late ‘70s (described more below).

America therefore gave U.S. manufacturers little recourse but to set up shop overseas, where they could get around the onerous the import restrictions placed by other countries and take advantage of low-cost labor. Smaller players that couldn’t afford to expand internationally were choked out domestically by cheaper subsidized goods coming in. As a result, manufacturing, this cornerstone of American society and identity since the early 1900s, peaked in the 1970s and subsequently began its long march downwards.

But what has filled the wake of manufacturing? Where does our labor identity now lie? According to elites, the cheerful answer is the “services sector” and “knowledge economy,” but according to the non-elites, the answer is perhaps a bit more grim. Here, let’s return to the financialization and softwarification of America described in the previous section. The problem with high finance and software engineering is that, unlike manufacturing, they aren’t accessible to many Americans today, leading to an erosion of the once-stable American middle class and a widening between the haves and have-nots.

Moreover—and controversially?—finance perhaps isn’t exactly… technologically innovative or generative in the same way manufacturing physical products might have been? And software, as discussed, has been a bright spot to the decline of American dynamism, but it alone doesn’t make up for other lackluster areas of 0 → 1 innovation in technology, as I’ve also written about previously.

All in all, while a deeper exploration is absolutely necessary here, my sense is that globalization led to the decline of the manufacturing, which led to a shift in our labor identity towards finance and software, which not only left the middle class in the dust but also came at the expense of technological innovation.

IV. Economic shocks

In 1973, immediately following President Nixon’s request for Congress to make billions in emergency aid available to Israel for the Yom Kippur War, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) retaliated and instituted an oil embargo on the United States.

Disaster ensued. The price of gasoline in America quadrupled. Lines miles-long formed at gas stations, and fights intermittently broke out among those waiting in line. States instituted draconian gasoline rationing programs, and in 1974, President Richard Nixon signed the first national speed limit, restricting travel on interstate highways to 55 miles per hour.

To appreciate the full impact this had on the American psyche, we need to understand the central role that cars played in American culture at the time. “Everybody was completely dependent and in love with their cars as a symbol of American triumph and freedom,” says Meg Jacobs, author of Panic at the Pump: The Energy Crisis and The Transformation of American Politics in the 1970s. “The notion that Americans were going to run out of gas was both new and completely terrifying.” Indeed, it was a rude awakening. The realization that oil reserves were not endless, that technological development wasn’t entirely sustainable, and that a symbol of American self-conception was in decline ended the belief in limitless progress that had permeated the post-War era. The new ethos was one of survival.

Although the oil embargo ended in 1974, prices remained high. In 1976, Jimmy Carter came into office determined to manage the oil crisis, telling the nation that it was “the greatest challenge our country will face during our lifetimes.” Carter and Congress then spent the next two years putting together a weak bill that ultimately didn’t reduce our dependence on foreign oil.4 So in the summer of 1979, when OPEC announced yet another substantial price increase following the Iranian Revolution, American oil prices surged another 3x, bringing the American people once again to their knees. Long lines and fights re-appeared with a vengeance.

The lasting effects of oil, combined with lavish government spending on programs like the war, also ushered in a long period of inflation. While inflation had crept along at one to three percent for the previous two decades, it now exploded into the double digits. The unemployment rate was also nearing a dangerous ten percent line. Together, increasing inflation and increasing unemployment created the conditions for stagflation, an economic malaise that shook the American people for years to come.

V.

In 1979, at the close of the decade, President Carter delivered his “crisis of confidence” speech to the American people:

I want to talk to you right now about a fundamental threat to American democracy . . . It is a crisis of confidence. It is a crisis that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will. We see this crisis in the growing doubt about the meaning of our own lives and in the loss of unity of purpose for our Nation.

Carter held a mirror up to the American people. It was clear that by the time the decade was over, something had changed about us as a people. Indeed, contemporary author Tom Wolfe had already begun calling the 1970s the “Me Decade,” one where Americans turned inward and focused their attention on themselves rather than on communal problems of politics or social justice. Things became about sustenance over growth, paralysis over progress, and cynicism over optimism.

The reception to Carter’s speech merely confirmed this. The people didn’t accept what they were seeing in Carter’s mirror. The media dubbed his address a “malaise speech” although Carter had never mentioned “malaise” once. Newspapers claimed that “there’s nothing wrong with the American people.”

And so brought the ‘70s to an ignominious end, with the government in disarray, our labor identity at the mercy of globalization, and Americans unable to process the closing of the frontier.

But the technological frontier still exists. It’s out there. And so far in the 2020s, we’ve witnessed industry taking a crowbar to the door and forcibly prying it back open. In 2020, SpaceX sent NASA astronauts back to space, the first time an orbital crew departed from American soil since NASA retired its space shuttle in 2011. Millions of Americans once again gathered in front of our screens to watch this historic moment. Before the end of the decade, Boom Supersonic will will be shuttling passengers from New York to London in 3 hours on a supersonic jet. Quantum computers are on the horizon, as qubit counts finally broke 3 digits earlier this year. And to round out 2021, we’ve witnessed a flurry of multi-billion-dollar fundings into nuclear fusion companies, which promise to eclipse the power of existing energy sources millions of times over, powering us into a green new world.

Things are happening again, and I’m here for it. I hope that in our long history, the ‘70s will just be an anomalous blip of a short chapter in an otherwise rich story of progress. I also hope—no, believe—that when we look back at the ‘20s (our ‘20s), we’ll see the start of a new chapter full of wide-eyed optimism and progress.

Thiel implicitly assumes that 0 → 1 innovation was a large contributor to pre-’70s growth. While it’s true that there was a lot of tech development (e.g., Apollo, ARPANet, quantum, nuclear, etc.), the torrid level of post-WWII growth until the ‘70s can also be explained by factors that aren’t 0 → 1 innovation. For instance, ‘60s growth was characterized by what economist Robert Collins calls “growth liberalism,” a period when Democrats and Republicans alike knelt together at the altar of economic growth. The JFK-LBJ tax cut, wage-price guidelines, tax credits, education and retraining programs, and efforts to keep interest rates low all contributed to such growth. While these policies surely also contributed to technological innovation to some degree, it’d be disingenuous—or at least incomplete—to say that technological innovation itself was a large driver to economic growth.

It’s also obviously possible that Thiel has already addressed this somewhere and that I haven’t done enough research.

After all, the China trade narrative doesn’t really begin in earnest until China joins the World Trade Organization in 2001.

Carter’s plan originally centered around a tax on oil consumption. However, Americans balked at a measure that would essentially amount to “Pay More, Buy Less,” and in 1978, Congress passed a watered-down version of Carter’s ambitions, the National Energy Act, which merely gave tax incentives for people to conserve oil.