This post is an initial effort at tying together some of my previous posts, including:

Corporate dictatorship and efficiency; The corporate nation-state

Post-RBG politics; Is it wrong to be friends with conservatives?; Principles vs. policies

But first, let’s use a recent tech scuffle as a starting point.

Facebook and NYU

Last week, Facebook issued a cease-and-desist letter to the NYU Ad Observatory to stop collecting data about Facebook’s political-ad-targeting practices. Here’s what the Ad Observatory was doing:

(1) I, a Facebook user, can download the NYU Ad Observatory’s Chrome extension and give the Ad Observatory permission to view the posts on my News Feed

(2) Whenever I’m on my News Feed, the Ad Observatory’s Chrome extension promises to scrape only the political advertisements on my Feed (nothing else!) and uses those ads for academic research

While the Ad Observatory’s Chrome extension seems okay at first glance (after all, who can be against supporting academic research?), I’m very sympathetic to Facebook here because this gives me flashbacks to Cambridge Analytica. Here’s what Cambridge Analytica did back in 2014:

(1) I, a Facebook user, can connect my Facebook account to a personality quiz app developed by a Cambridge University researcher. The app gives the researcher access to my personal data and also some data about my friends (thanks to Facebook’s API at the time)

(2) The Cambridge University researcher promises not to share the data with anyone and to use that data only for his own research.

Of course, you know how the story ended: The Cambridge University research broke his promise and handed the data, not only about me, but also about my friends, over to Cambridge Analytica.

The parallel between the Cambridge Analytica scandal and the NYU Ad Observatory is pretty clear: A seemingly trustworthy source is somehow getting access to personal and friend data and is making a promise about how it’s using that data.

When the Cambridge Analytica scandal came to light in 2018, the public shouted at Facebook to lock its data down and to build higher walled gardens around its data because bad actors abound. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission even entered a consent decree requiring Facebook to implement a “Mandated Privacy Program.” Under this “program,” Facebook must constantly be assessing the risk of “unauthorized access, collection, use, destruction, or disclosure” of sensitive data and “denying or terminating access” to sensitive data to third-parties that don’t comply with Facebook’s Terms of Service. People across the U.S. were adamant that Facebook must keep an iron grip over privacy and that it must stop others from stealing our data, even if those people “seem” trustworthy.

And that’s exactly what Facebook did. No developers, no advertisers, no academic researchers have your personal data, unless you give them explicit permission, and even then, the amount of data they have is miniscule. So, now, the NYU Ad Observatory is going behind Facebook’s back to get unbridled access to users’ News Feeds, and many of the people who were calling on Facebook to clamp down on user data are also now angry at Facebook for sending the cease-and-desist. What do they want? To have their cake and eat it too?

To be clear, I’ve always been a big fan of data interoperability and would like Facebook to lift some of its privacy controls because data sharing can lead to increased innovation and research. And I personally think Facebook should build sophisticated data access APIs to enable the NYU Ad Observatory to research what political ads people are seeing in their News Feeds. The correct, productive plane of debate here is very narrow: How can Facebook safely develop tools or procedures for third-parties to establish trust (with Facebook / users) and access subsets of user data? But to broadly slam Facebook for failing to take privacy seriously and then to broadly slam Facebook for taking it too seriously is giving me whiplash.

Power is king

In Ben Thompson’s excellent post on this whole series of events, he concluded by saying:

[T]he loudest objectors to Facebook’s cease-and-desist letter are the same folks that applauded the FTC’s consent decree, were aghast at Clearview AI, and still hold up Cambridge Analytica as a scandal; consistency isn’t their strong suit. To that end, Facebook should have taken a far more political approach to this issue . . . [R]ight-and-wrong, at least when it comes to this issue, is not about rules and consistency, but about who says it is such. Facebook has little choice but to play the game.

Power is king, and principles are the philosopher. The philosopher advises the king on how the king should rule his kingdom. To the extent that the philosopher tells the king what the king already wants to hear, the king happily follows the philosopher’s advice and issues royal edicts proclaiming that he has backing from the philosopher. But where the philosopher’s advice is inconvenient, the king doesn’t hesitate to have the philosopher executed. Meanwhile, he searches his kingdom for another philosopher that will whisper in the king’s ear exactly what the king wants to hear.

In other words, people are ready to abandon their principles for power. Or, to be even more explicit, for many people, their number one principle is the accumulation and exercise of power in their favor.

The obsession with power explains the frustrating incoherency in many people’s positions about Facebook, perfectly exemplified in the anger over this incident with the NYU Ad Observatory specifically and over the company’s strategies broadly. In fact, this obsession can explain much of the polarized social milieu we live in today. Everything is about power, and we’re willing to sacrifice our social capital, create walls of stubbornness, and forgo our intellectual honesty for the accumulation of power. Mitch McConnell knows this, and his shepherding Amy Coney Barrett through the SCOTUS nomination process is only the latest chapter in his power-hungry quest. Progressives are also picking up on this as they see Court-packing as a foregone conclusion for what Biden should do to the Court if he wins the election.

What’s striking about Thompson’s excerpt above is that he not only acknowledges that those in politics lack principles, but he also uses that truth to contextualize what Facebook’s response should be: Facebook should “play the game.” In other words, Facebook needs to pander to power. Again, to be even more explicit, power shapes, warps, and sharply limits the permissible range of thought and expression for companies and people in the public eye.

To be clear, I don’t disagree with this conclusion. After all, this is what public relations and marketing departments are designed to do. Once a company (or a famous individual) becomes big enough and attracts the eye of power, it needs to engage PR and marketers to ensure that all of its actions appeal to the people in power.

Companies, people, entities, whatever, all kneel to the influence of power, lest power act against them. It’s the truth, but it’s a sad truth. If you want to develop independent, strong convictions about the world, you need to distance yourself from the locus of power. Otherwise, if you’re too close to power, it unduly influences the way you think and act. This is perhaps another way to frame Clay Christensen’s famous theory of disruption. Large companies eventually stop innovating because their power blinds them to the promise of transformative technologies that can serve users in different ways. Scrappy startup companies, unencumbered by the burden of power and free to view the world through a diversity of lenses, identify new avenues for experimentation and “disrupt” the powerful incumbent.

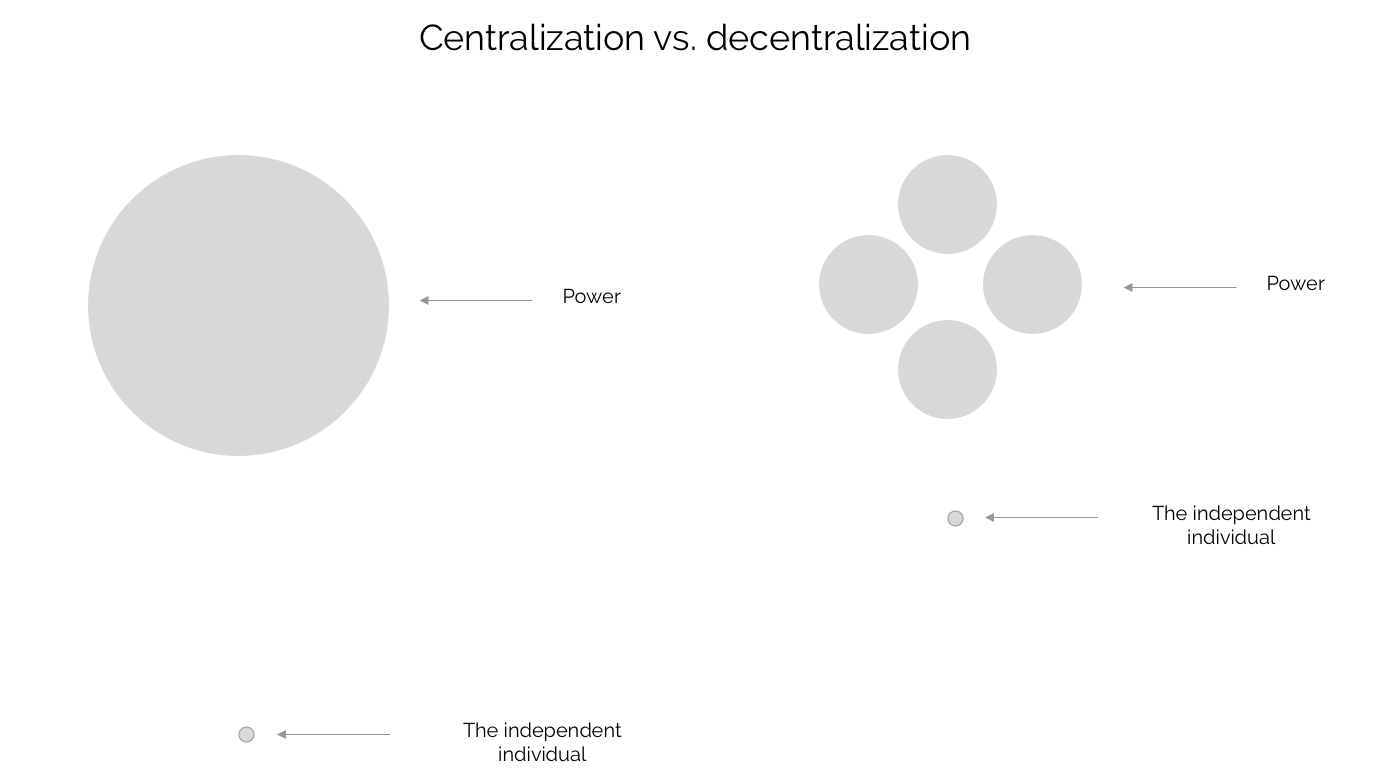

Here are two ideas for thinking about how much you need to distance yourself from power in order to be independent. First, increasingly dominant power will increasingly dominate public discourse and thought. So, all else equal, the more that power becomes centralized, the farther you need to distance yourself from it in order to achieve independence. Likewise, in the opposite direction, the more that power becomes de-centralized, the closer you can afford to come to it while remaining independent.

Second, increasingly polarized power will increasingly shun identifiable individuals that don’t fit neatly into one of the buckets of power. So, all else equal, the further polarized the locus of power is, the farther away you need to be from it. The less polarized the locus of power is, the closer you can afford to come to it.

These ideas about power and independence help to explain my sympathy for fringe ideas (detailed in Facebook bans QAnon), my distaste for polarization (detailed in Is it wrong to be friends with conservatives? and De-polarizing the Supreme Court), my skepticism of power (detailed in Corporate dictatorship and efficiency and The Facebook naysayer conundrum), and my desire and respect for consistent principles (detailed in Principles over profits).

📚 What I’m reading

To do politics or not do politics? Tech start-ups are divided.

Six Republican Secretaries of State tried to stop Facebook’s effort to register millions of voters. The headline doesn’t include the Republicans’ issue, which is that some of Facebook’s voting registration information is allegedly false. While that is certainly a valid concern, there also seems to be an element of Republicans saying, “Stay out of this, we can take care of it,” which I find extremely paternalistic and annoying.

Forecast 2025: China Adjusts Course. This past week, the Chinese Communist Party finalized China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (FYP), spanning 2021–2025. Although this FYP won’t be released until March, this China think tank made some predictions. The report is long, but the most interesting sections to me were the ones on Chinese Politics and Chinese Technology.

Six lessons from six months at Shopify.

Facebook’s Oversight Board (i.e., Supreme Court) starts hearing cases.

Apple is building an alternative to Google search. I have mixed feelings about this. On one hand, yes, Google is facing increasing scrutiny around privacy, and politicians are wondering whether Google being the default search engine on iOS is evidence of antitrust violation. So, this might seem like as opportune of a time as any for Apple to step in and try to build its own search engine. On the other hand, I wonder if Apple has better things to do with its time and money. From the article: “But with profits this year predicted to exceed $55bn and $81bn of net cash reserves at the last count, Apple can afford to make long-term investments.” Yes, but long-term investments into search? Really? My intuition is that the investment would be better spent on things more Apple-like, like AR glasses. Not sure.

And finally, here’s an image that accurately sums up this year: